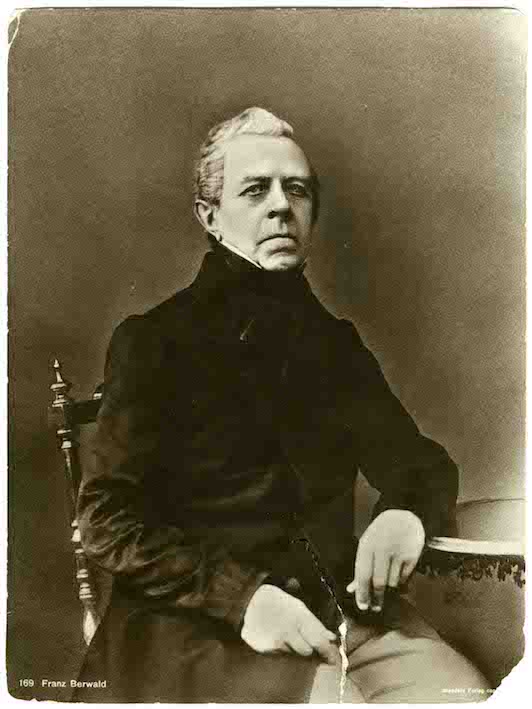

Franz Adolph Berwald, born 23 July 1796 in Stockholm, died 3 April 1868 in Stockholm. Composer, violinist, teacher, orthopaedist and industrialist, Franz Berwald was the leading composer of symphonies in 19th century Sweden. Violinist and violist with the Royal Court Orchestra 1812−18, 1820−23 and 1824−28. Teacher of composition and orchestration at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Stockholm 1867−68. Honorary member of the Mozarteum University of Salzburg 1847. Elected into the Royal Swedish Academy of Music 1864 as member no. 386.

Life

Background, early years and studies

Franz Berwald was from a north German musical family that arrived in Sweden with his father Christian (1740−1825) and paternal uncle Georg Johann Abraham (1757−1825), both of whom, having studied in Berlin for Franz Benda amongst others, had been employed as violinists in the Swedish Hovkapellet (the Royal Court Orchestra), the former in 1773 and the latter − who was also a bassoon virtuoso − in 1782. Georg’s son Johan Fredrik (1787−1861), Franz’s cousin, was a talented violinist and would, after a stint in the Russian imperial court orchestra, become concert master for the Swedish Hovkapellet in 1812, advancing to hovkapellmästare (chief conductor of the Royal Court Orchestra) in 1823. Christian Berwald, who left the Hovkapellet in 1806, was also a violin teacher and sheet music copyist, and ran a sheet music lending library. His wife since 1789, brewer’s daughter Agneta Bruno (born 1766 in Stockholm), passed away in 1809 and when his father died in 1825, Franz was left in charge of the financial affairs of his three unmarried sisters.

"Franz Berwald the child prodigy" silk embroidery, detail, needlework probably by his sister Agneta Charlotta. (Nordiska Museet)

Franz started to play violin at the age of five and received his first music lessons from his father, who was soon able to promote his son as a prodigy. The young Franz performed at a court concert in 1805 and the year later as a soloist in concertos by Johann Schobert and Giovanni Mane Giornovichi in Uppsala, Västerås and Stockholm. In March 1811 he appeared as solo violinist in Stockholm for a performance of a violin concerto by Edouard Du Puy, who became his teacher for a while. In 1812 Du Puy was made hovkapellmästare, and Franz was taken on by the Hovkapellet, where, with the exception of a break in 1818−20 and for the 1823−24 season, he served as a violinist and, as of 1815, violist until 1828. His younger brother August (1798−1869) was accepted as a violinist in 1815, and the two would often perform together.

First steps as a composer

Even though Berwald probably received a certain degree of theoretical education from Du Puy, he is usually considered an autodidact as a composer. However, it is entirely conceivable that he was given technical advice by his cousin Johan Fredrik and hovkapellmästare Joachim Nicolas Eggert (who left Stockholm, however, in 1812). He would have been able to make countless observations of compositional and instrumental technique from his place in the Hovkapellet, and he also helped his father to notate. In 1816 Berwald wrote Theme and variations for violin and orchestra on a theme that ‘imitates’ one by Pierre Rode on which he himself had written a variation. The piece is also stylistically reminiscent of Rode’s compositions. The following year saw a now regrettably lost Fri fantasi ‘on a national theme’ for orchestra, a concerto for two violins and orchestra, and a septet for clarinet, bassoon, horn, violin, viola, cello and double bass − the same setting as for Beethoven’s op. 20. The three pieces were performed with much success at a concert with the Hovkapellet in Börssalen (the grand hall of the Stockholm Stock Exchange) on 10 January 1818, with the double concerto played by the composer and his brother August. It was repeated at a concert on 5 November that year, and the fantasy and quartet were performed again at a concert on 7 December 1819.

In the autumn of 1818 Berwald worked on the publication of a Musikalisk Journal, which ran for six issues in the following year. In it, he published some of his own songs and piano pieces, alongside the latest material from abroad. He also composed two string quartets, one in G minor and one in B-flat major (this latter now lost). In the summer of 1819 the Berwald brothers undertook a concert tour of Finland and Russia, and it appears that Franz’s Theme and variations was given its debut performance in August in Åbo, presumably with the composer himself on solo violin. In the hope that his musical journal would be noticed outside Sweden, he changed its name for the four issues that came out in 1820 to Journal de Musique. In 1819, he composed orchestral variations on the song ‘Göterna fordomdags drucko ur horn’, which was performed on 7 December before being lost to posterity, and a quartet for piano and winds. In some parts of his journal Berwald demonstrates little more than a command of the opera-esque style of his time, but works such as the septet and the G minor quartet already possess a distinctly personal tone.

Pastel drawing by anonymous 1837. (Musikverket)

Idiomatic consolidation

A concert in Stockholm on 3 March 1821 featured the debut performance of the piano quartet along with a symphony in A major and an extrovert, occasionally virtuosic violin concerto in C-sharp minor, with his brother as soloist; of the symphony only parts of the first movement have been preserved. This represented a further consolidation of Berwald’s tonal idiom and the critics, this time, were merciless − according to the anonymous reporter in Argus the composer ‘had, in his quest for originality and his endeavours only to impress through grandiose effects, wilfully banished all melody from his compositions’. The review prompted a pithy polemic from Berwald, who claimed that the work ‘has been written in its own peculiar style’ and that art must go further than the ‘preservation of the past’. He received the royal commission to write a cantata for the unveiling of a statute of King Charles XIII on 5 November 1821. The work was performed at a concert in Börssalen on 29 January 1822 along with his double concerto, which was executed by August and their sister Carolina. Another cantata, also with orchestra, to celebrate the arrival of Crown Princess Josephine to Sweden ahead of her marriage to Crown Prince Oscar, was written in 1823. The almost jocular Serenade for tenor and six instruments was composed in 1825, but of this only fragments remain.

This serenade and the cantata for the Crown Princess were performed at a concert in the Börssalen on 8 April 1826, and in the summer of the following year, Berwald and pianist Jan van Boom made a brief tour of Norway. 1827 also saw a Concert-Stück for bassoon and orchestra, which includes a variation movement on ‘Home, sweet home’. Berwald also worked on an opera, Gustaf Wasa, in which he had the brazenness to compose new music to Kellgren’s libretto for Naumann’s ‘national opera’. The concerto and a concert version of the first act of the opera were performed in 1828, and the opera act again at the Kungliga Teatern (the Royal Opera) on 15 May; a march from the work was published for piano by Berwald himself. Two concerts in November and December that same year gave him an opportunity to present parts of the opera’s second act, including the hymn ‘Ädla skuggor, vördade fäder’, plus the battle painting Slaget vid Leipzig and a ‘new’ septet, which turned out to be just a reworking of its predecessor.

In Berlin as a composer − and orthopaedist

On several occasions, Franz Berwald had applied in vain for scholarships to study abroad, and the application he made in 1828 was also rejected. Despite this, he left the Hovkapellet, raising the funds he needed for his trip with the two autumn concerts, which he supplemented with a modest subsidy from Crown Prince Oscar.

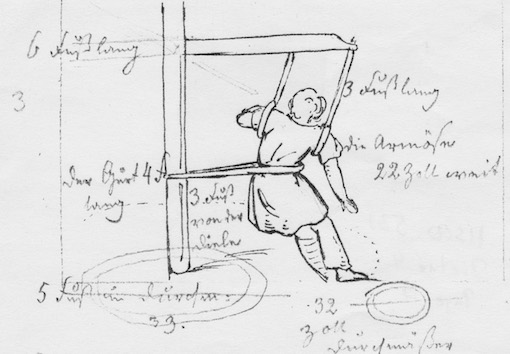

Berwald chose Berlin, where he would stay until 1841. At first, he tried to launch his music and worked on several opera projects, most arduously Leonida and Donna Isabella. Of the former, he was able to dispatch three numbers to Stockholm for performance in 1830. At the same time, he submitted a completed score for Leonida, without success, to the board of the Berlin opera. An idea for a new opera, Der Verräter, which was mentioned in 1834, seems to be a reworking of Leonida. During these early years in Berlin, Berwald also spent his time self-studying counterpoint using Cherubini’s recently published textbook. Unfortunately, he failed to make any suitable connections in the Prussian capital and thus also to have his music performed. In 1835 he rekindled an old interest and embarked on a completely different career as an orthopaedist, working at an institute that he both founded and equipped with mechanical apparatus of his own devising. After having received a testimony from one of Berlin’s leading anatomists, Berwald’s institute became a successful and secure source of income. He banked on his Leonida/Der Verräter being staged in Stockholm in the autumn of 1837, when a Swedish translation was ready and the music for the different parts written out, but his hopes came to nothing. He continued his orthopaedic practice in Berlin until 1841, when he left the city to try his fortunes in Vienna.

Between 1835 and 1841 Berwald was the head of an orthopedic institute in Berlin where he designed "Swedish physiotherapy" equipment. (Musikverket)

His Vienna venture and commitment to Sweden

On 18 July 1841, Franz Berwald married Mathilde Scherer, the assistant he had taken on at his clinic in 1836. He was now in Vienna and intending to combine composing and orthopaedics; but his urge to compose proved too overpowering and he ended up writing the orchestral works Elfenspiel, Humoristisches Capriccio and Erinnerung an die norwegischen Alpen, all three of which were performed at a charity concert in Vienna on 6 March 1842 to almost unanimous acclaim. Humoristisches Capriccio has not survived but it has been assumed that Berwald, who was known to recycle his thematic ideas (a passage in Erinnerung is taken from Leonida for example), could have used parts of the piece for the overture of his later opera Drottningen af Golconda. He also worked on his opera Estrella di Soria and his Sinfonie sérieuse, which is definitively dated in Vienna. However, by mid-April 1842, Berwald was back in Stockholm, where on 19 May he held a concert in Ladugårdsland Church, at which the above three orchestral works were accompanied by two numbers from Estrella, a chorus from Der Verräter, the newly written Ernste und heitere Grillen and ‘by request’ his Slaget vid Leipzig.

The summer of 1842 he spent in Nyköping, where he composed the tone paintings Bajaderenfest and Wettlauf as well as a Sinfonie capricieuse, which is said to have existed as a complete score that has since been lost. A detailed orchestral sketch for a work of this name has been preserved, but it is unsure whether it represents the work from 1842 or a completely different one in the same key (D major). He completed his ‘operetta’ Jag går i kloster in October that same year, a couple of numbers from which could be heard at his concert in the Börssalen on 6 December along with Erinnerung an die norwegischen Alpen and Bajaderenfest. Ahead of the capital’s celebrations of King Charles XIV John’s silver jubilee on 6 February 1843, Berwald was commissioned to write some festive music, producing a Grande Polonaise that was published as a piano arrangement and subsequently inserted into Estrella di Soria. He wrote a new operetta, Modehandlerskan, in the summer of 1843, and on 2 December a concert-cum-opera performance was held at the Kungliga Teatern that included, in addition to works by Mozart and Haydn, his Erinnerung an die norwegischen Alpen, Bajaderenfest, an aria from Modehandlerskan, Sinfonie sérieuse and finally Jag går i kloster, to which Jenny Lind contributed. This event has become renowned mainly for the scathing criticism of the symphony, but there was also much speculation that Johan Fredrik Berwald, in his capacity as hovkapellmästare, had treated his cousin’s compositions with a degree of indifference. True, the warmly received operetta ran for another five performances − the second occasion with the symphony’s first movement ‘by request’ − but the poor response to the symphony as a whole gave Berwald cause to revise the work and to never present any of his other symphonies in public again.

Berwald, 1862.

In 1844 he wrote a tone painting for four-handed organ, En landtlig bröllopsfest, and held a concert in the Great Church in Stockholm on 19 November that is said to have drawn an audience of some 3,000 people, attracted by the promise of three new patriotic shorts − ‘Swea, hjeltemodren satt …’ (printed under the title ‘Konung Oscar!’), ‘Himmel, skydda Svea land’ and ‘Svenska folk i samdrägt sjung!’; this last song, which had lyrics by Herman Sätherberg, was intended by Berwald as a new national anthem and already published. In early 1845 he composed both his Sinfonie singulière and the symphony in E-flat major. Then on 26 March he oversaw the debut performance of Modehandlerskan, which despite the involvement of Wilhelmina Fundin and Julius Günther was a complete fiasco and survived only that one evening. In the summer Berwald published two important opinion pieces in the newspaper Aftonbladet titled ‘Some thoughts upon the young composers of today’ and ‘A discourse on the teaching of music in our public schools etc.’ That autumn he gave a concert at which the aforementioned organ work and the newly written cantatas Karl XII:s seger vid Narva and Gustaf Adolf den Stores Seger och Död vid Lützen were performed. To this category of calculated populism belongs Nordiska Fantasie-Bilder for soloists, choir, winds and organ, which was performed at his concert in the Great Church on 9 May 1846, and Gustaf Wasas färd till Dalarne from 1849, which remained unperformed until 1866 when it was dubbed a ‘romantic tone painting’.

Into Europe and his retreat as factory manager

In the summer of 1846, Berwald took himself abroad again, stopping off en route in Gothenburg to hold a concert of some of his latest works, including En landtlig bröllopsfest for which he was one of the organists. He tarried for a while in Paris, but failing to have his music established there, decamped at the end of November to Austria. Here, on 26 January 1847, he gave a concert at the Theater an der Wien of two of his tone paintings, two of his cantatas and the debut performance of his new singspiel Ein ländliches Verlobungsfest in Schweden, a work largely based on folk tunes and simultaneously published in Vienna that featured its dedicatee Jenny Lind as one of the soloists. Berwald went on to give concerts in Linz, Salzburg, Graz and Nuremberg until 1849. In December 1847 he was made a member of the Mozarteum in Salzburg, and in 1849 he applied, again in vain, for the position of director musices in Uppsala − a misfortune that was repeated later that year when his cousin vacated the post of hovkapellmästare. Berwald completed a new version of Estrella di Soria in 1848 and sketched two string quartets, one in E-flat major and one in A minor, which he finished the following year. He also wrote his first piano trio in 1849, completing it on his return to Stockholm in May.

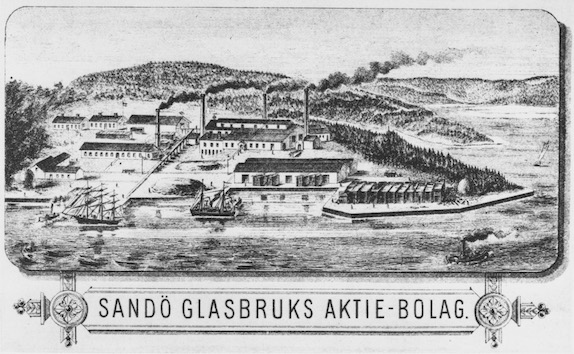

Without employment as a musician, Berwald once again had to seek other means of earning a living. In 1850, through the machinations of his friend Ludvig Petré, he became general manager of Sandö glassworks on the Ångermanälv river north of Härnösand. Berwald proved to have practical as well as financial sense, and in 1853 he became a partner of the company and a stakeholder in a sawmill in the same town. He was most often in Sandö in the summer months, spending the winter in Stockholm working on his compositions. In 1851 he produced two piano trios, in 1853 his first piano quintet and another piano trio. He tried out his chamber music pieces in a small private circle that included such fellow musicians as Oscar Byström, Ivar Hallström and Conrad Nordqvist. Berwald also had a few pupils, the most famous being pianist Hilda Thegerström, for whom he arranged further study with Franz Liszt, and singer Christina Nilsson. He dedicated his piano concerto in D major from 1855 to Hilda Thegerström, and his second piano quintet of 1857 to Liszt. The piano concerto is a flagrantly romantic and extravagant work that is so constructed as to be performable by a lone soloist. At the end of the 1850s he also wrote the duos for piano and, respectively, cello and violin, and published most of the above chamber works in Germany, where they were often lauded by the critics. Three ambitious piano pieces, including the subsequently published Romanze et Scherzo, also belong to this period.

Sandö Glassworks Ltd. Copper plate engraving. ("Franz Berwald. Die Dokumente sienes Lebens", Monumenta Musica Svecicae; Bärenreiter, Kassel, 1979).

When Sandö ended up in financial difficulties in 1858, Berwald was given a similar position at the Sandvik glassworks in Bromma, but left the following year. On 9 April 1862 he finally got to see his Estrella di Soria given its premier staging at Kungliga Teatern in a revised version that was apparently completed in the spring of 1861. Despite this, he continued to make changes right up to the eleventh hour, even between performances. The work is a veritable grand opéra with elements of buffa that tells of love and war in 15th century Castile. The original German libretto was written by Viennese playwright and poet Otto Prechtler, who had also supplied the lyrics for Ein ländtliches Verlobungsfest. It was performed at the Kungliga Teatern with Ludvig Norman conducting and Fredrika Andrée in the demanding title role. The work ran for only five evenings but was received with remarkable praise and inspired further opera plans from Berwald, who went on to sketch Slottet Lochleven on the fate of Mary Stuart as recounted in Walter Scott’s novel The Abbot.

Late acknowledgement

In January 1864, Berwald was voted into the Kungliga Musikaliska akademien (the Royal Swedish Academy of Music), a full twenty-two years after the initial proposal, and when a new professorial chair in composition was established at the academy’s conservatory in 1867 he applied for the position; yet again he was passed over, but this time it incited such a strong reaction that the appointed professor Hermann Berens − who had already been teaching composition at the conservatory − withdrew to make way for Berwald. As professor he was tasked with launching a revision of the Swedish hymnal, and started writing a work on compositional theory. By 1864 he had completed his opera Drottningen af Golconda, which, like other composers before him, he based on a tale from the world of myth and legend. He used material from Slottet Lochleven in this apparently rather hurried work, conceiving the title role, with its rich coloratura, for his pupil Christina Nilsson. The Kungliga Teatern accepted the work, but it was never staged. While it was eventually heard for the first time in a concert version in Gothenburg in 1933, it would be a long while before the Stockholm opera put on the scenic version, which it finally did in 1968 to mark the first centenary of the composer’s death.

Berwald also composed in 1864 an Apoteos till firande af 300-årsminnet af Shakespeares födelse, and in 1866 another cantata, Hymn och jubelsång, to lyrics by Oscar Fredrik (later King Oskar II), for the opening of the Stockholm Exhibition of Industry and Art. By reason of a parliamentary resolution on representational reform, he set to music a text by Frans Hedberg and composed ‘Den 7 December 1865. Echo från när och fjärran’ for soprano, clarinet and piano, which was performed with earlier works at his last concert in the Great Church on 5 April 1866. In the 1850s and 60s he was a prolific writer of articles for the press and commentator on the social and economic problems of his time. He continued to voice his opinion on musical matters, often as a critic. Franz Berwald died of pneumonia after eight days of illness on 3 April 1868.

Franz Berwald 1796-1868, relief.

Works

Berwald ranks as our leading 19th century composer of symphonies. His orchestral pieces, the septet and string quartets all belong to the living repertoire, and it is also here that his distinctive style is most clearly manifest. His headstrong devotion to opera was de rigueur for the time, as it was as a composer of such works that one could earn both international repute and a successful living. Berwald’s most important stage work, Estrella di Soria, which was revived without much success by the Kungliga Teatern in connection with the opening of the new opera house in 1898−1900, has now, like many of his concert works, piano quartets and piano trios, become popularised through recordings. While the more time-bound works, such as the cantatas, are no longer able to garner any interest, several sections from his other stage creations are worthy of attention, as are some of his relatively few songs, such as ‘Andenken’ (Friedrich von Matthisson), ‘Aftonrodnan’ (Georg Ingelgren) and the lullaby ‘Ute blåser sommarvind’ (S.J. Hedborn), all of which appeared in his Musikalisk Journal in 1819, as well as ‘Des Mädchen Klage’ (1831, Friedrich Schiller) and ‘Traum’ (1833, Ludwig Uhland).

Unlike many of his contemporary songwriters, Berwald rarely approached the folk sound, despite its manifest influence on works like Erinnerung an den norwegischen Alpen and, dominantly so, Ein ländtliches Verlobungsfest. His earlier songs, as well as his initial concert works, are marked by the predilection for French opera that prevailed at the Kungliga Teatern after the turn of the 1800s, and that was much cherished by Du Puy. If Berwald’s more ephemeral material can sometimes seem rather superficial, it is, strictly speaking, due to his fixation on genre, for it too exhibits sterling craftsmanship.

It has been said that in his vocal pieces Berwald treats the voice instrumentally, but it is more the case that he demanded a certain matter-of-factness that clashes at times with the romantic impulse. A similar freedom from effects characterises the ‘impractical’ − as many critics have complained − piano parts of his chamber music, since they are meant to function in their compositional contexts rather than develop some kind of playable tonal grandeur. This balance between an external expressiveness and an inner absolute-musical bearing is also characteristic of his symphonies, in which the motifs are treated with vigour, while the orchestration is forever in the service of the form pattern. He built on the Beethovian symphonic line, creating, despite certain influences from Mendelssohn, Weber and Spohr, with his individual, often truncated themes, a wholly personal compositional style that stretches the classicist parameters with its increasingly consistent and refined development technique that can be described as liberally applied counterpoint and that is underpinned by the orchestral sound. This exactitude is often bound up with a capriciousness that manifests itself in wilful melodic or rhythmic fancies, always with a fresh dose of spirituality.

The same thematic density and the same gushing elegance characterises Berwald’s ‘tone paintings’, especially Elfenspiel and Ernste und heitere Grillen. In his original autograph of the latter he had included several new, almost decorative ideas that are incorporated into the later printed scores. Erinnerung an die norwegischen Alpen was given a somewhat more emotional character that, as in his symphonies, is allowed to express itself with a certain austerity in the slow movements of Sérieuse and Singuliére and come into full bloom in the lyrical slow movement of the E-flat symphony, the melody of which is taken from his En landtlig bröllopsfest for organ, one of many successful self-quotes to which Berwald occasionally treated himself. Smaller such borrowings in the later works can be explained by his despairing of an earlier work’s success and his consequent recycling of its material. Yet in never breaking loose of their new contextual totality they prove just how unique his idiom is, although at times, the classicist reference can contribute to some tiresome phrasal repetition, as in the overture to Jag går i kloster and the finale of (the reconstructed) Sinfonie capricieuse. He can also use rhythm or a rhythmic pattern to the point of obstinacy, and his sequence technique can be far too blatant.

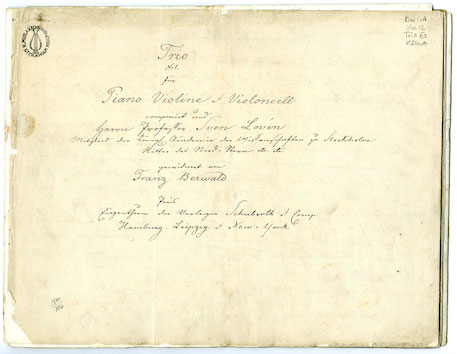

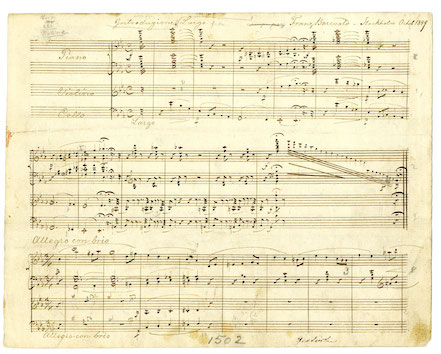

Titel page and opening of Trio no. 1 in E-flat major for piano, violin and violoncell. Berwalds autograph.

What otherwise distinguishes Berwald’s firm sense of genre is the way his mind works orchestrally in his orchestral pieces and chamber musically in his string quartets and piano trios, even if his themes with their rhythmic profiling can recur in different works. Berwald’s harmonic structure is primarily classicistically strict and reaches barely beyond Spohr’s, but in some of the later chamber music works he applies rather bold chromatics. An unusual key-change gambit is presented in the first movement of Sinfonie sérieuse, in which the recapitulated main theme appears in A minor instead of the movement’s principal key of G minor.

Berwald’s deliberate sense of form is revealed not least in his many experiments with the concept. In both Sinfonie sérieuse and Sinfonie singulière he returns in the finale to elements from the slow movements, while in the latter − as already in the 1828 septet − the scherzo is embedded in the slow movement. In the finale of the E-flat symphony, the principal theme does not return, but is ‘replaced’ by a new idea when the recapitulation begins. The entire E-flat major string quartet is fashioned like a ‘Chinese box’, in which the scherzo is contained within the slow movement, which itself is contained within a sonata-like Allegro movement. In the C minor piano quintet, a scherzo is built into the first movement, with its secondary theme re-emerging in the finale. Like many of his contemporaries, Berwald insisted that the movements of the multi-movement works were to follow on from each other seamlessly, as was the case already in the double concerto from 1817. In the piano trios he even composed transitions between the movements.

Influence and reception

In his composition classes from 1867−68, Berwald had five pupils: Johan Alfred Ahlström, Joseph Dente, Oscar Hylén, Conrad Nordqvist and Marie Louise Öberg, all of whom would, each in their own way, make their mark on Swedish music. On the other hand, there are few Swedish composers who can be said to have been directly influenced by his style. While the only one to exhibit any obvious Berwaldesque traits is Oscar Byström, traces of Berwald can also be discerned in, for example, Norman and Stenhammar.

If Berwald’s output was not fully appreciated in his lifetime, a positive response can already be detected after Norman’s performance of Sinfonie sérieuse in 1871. Norman debuted the E-flat major symphony in 1878, and by the turn of the century a good many important musicians were enrolled in the revival of Berwald’s music, amongst them Tor Aulin (who gave the first performance of Sinfonie singulière in 1905), Wilhelm Stenhammar and Henri Marteau. A Franz Berwald Foundation, which lasted from 1909 to 1947, carried on the publication of many of his unprinted works, accompanied in these endeavours from 1940 by the Föreningen Svenska Tonsättare (the Swedish Society of Composers). This, in turn, had a certain impact abroad, but it was really only with Igor Markevitch’s recordings of two of Berwald’s symphonies in 1956 that the process can be said to have been consummated; the many recordings that ensued speak for themselves. Berwald’s collected works were published between 1966 and 2014 in 30 volumes, the product of a joint venture by the Kungliga Musikaliska akademien’s Monumenta series and Bärenreiter-Verlag, with a Documenta volume being added in 1979.

Lennart Hedwall © 2015

Trans. Neil Betteridge

Publications by the composer

Musikalisk Journal 1−6, 1819.

Journal de Musique 1−4, 1820.

'Anvisning till studier i kontrapunkt, fuga, komposition och orkesterstämföring' [incomplete].

Numerous articles on music etc.

Bibliography

Ander, Owe: ‘Berwalds världsliga kantater’, Artes, no. 1 1996.

−−−: ‘Svenska sinfoni-författares karaktäristiska orkester-egendomligheter’. Aspekter på instrumentations-, orkestrerings- och satstekniken i Berwalds, Lindblads och Normans symfonier, diss. in musicology, Stockholm University, 2000.

−−−: ‘In the Halls of Triumph. The Secular Cantatas of Franz Berwald’, in: Hans Åstrand (ed.), Berwald-Studien, Stockholm: The Royal Swedish Academy of Music, 2001.

−−−: An Inventory of Swedish Music vol. III. Twenty 19th-Century Composers from Du Puy to Söderman, Stockholm: self-published, 2013.

Andersson, Ingvar: Franz Berwald, Stockholm: Norstedt 1970. New edition Stockholm: Edition Reimers, 1996.

Arosenius, Alfhild: Glimtar ur Franz Berwalds liv, Bäckahästen, vol. 2, 1946.

Aulén, Gustaf: ‘Till 150-årsminnet av Franz Berwalds födelse. Tal vid Berwaldskonsert i Uppsala universitets aula den 22 okt. 1946’, STM, vol. 28, 1946.

Baeckström, Arvid: Franz Berwalds sista replik i hans första tidningspolemik, in STM, vol. 32, 1950.

Berwald, Franz: Sämtliche Werke, Monumenta Musica Sveciae / Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1966−2014. [Includes liner notes.]

Franz Berwald. Die Dokumente seines Lebens, Erling Lomnäs (red.) et al., Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1979. [Supplementary volume to Franz Berwald, Sämtliche Werke, Monumenta Musica Sveciae / Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1966−2014.]

Brandel, Åke: ‘Släkten Berwald − dess tidigare historia och dess verksamhet i Ryssland’, STM, vol. 43, 1961.

Broman, Sten: ‘Berwalds instrumentalmusik före 1830. En kort översikt’, Musikvärlden, no. 3 och 8 1945, no. 1 1946.

−−−: ‘Franz Berwald’, in: The Royal Opera's programme leaflet to Drottningen av Golconda, Stockholm, 1968.

−−−: ‘Franz Berwalds stamträd’, STM, vol. 50, 1968.

Castegren, Nils: ‘Musikaliska Konstföreningen och Franz Berwald. Bidrag till kännedomen om offentliggörandet av Franz Berwalds verk intill 1911’, in STM, vol. 35, 1953.

−−−: ‘Franz Berwald. Overtures & Tone Poems’, liner notes to CD edition, Nonesuch H 71218, 1968.

−−−: ‘Franz Berwald och hans tre drottningar’, in: The Royal Opera's programme leaflet to Drottningen av Golconda, Stockholm, 1968.

−−−: ‘Franz Berwalds kompositionselever vid Musikkonservatoriet 1867−68’, STM, vol. 56, no. 1, 1974.

Dahlgren, Fredrik: Förteckning öfver svenska skådespel uppförda på Stockholms theatrar 1737−1863, Stockholm: Norstedt, 1866.

Dale, Kathleen: ‘Franz Berwald’, The Listener, vol. 21, 1950.

Eppstein, Hans: ‘Franz Berwalds septett − fakta och frågor kring verkets tillkomst’, STM, vol. 67, 1985.

−−−: ‘Franz Berwald. Kammarmusik’, liner notes to CD edition, Musica Sveciae MSCD 521, 1989.

−−−: ‘Franz Berwald’, in: Leif Jonsson (ed.), Musiken i Sverige, vol. 3, Stockholm: Fischer, 1992.

−−−: ‘Fragen zu Berwalds instrumentaler Kompositionstechnik’, in: Hans Åstrand (ed.), Berwald-Studien, Stockholm: The Royal Swedish Academy of Music, 2001.

Erdmann, Hans & Heinrich W. Schwab: ‘Beitrag zur Geschichte der Musikerfamilie Berwald’, Die Musikforschung, vol. 23, no. 2, 1970.

Eriksson, Torbjörn: ‘Franz Berwald. Estrella di Soria’, liner notes to CD edition, Musica Sveciae MSCD 523, 1993.

Estreen, Per: ‘Något om Berwalds ungdomsverk för piano’, STM, vol. 28, 1946.

Gefors, Hans: ‘Är det konstigt att Franz Berwald aldrig blev känd?’, in: Sten Hanson & Thomas Jennefelt (eds), Tonsättare om tonsättare, Stockholm: Edition Reimers, 1993.

Hallgren, Karin: ‘Berwald’s Cantatas from the 1840’s’, in: Hans Åstrand (ed.), Berwald-Studien, Stockholm: The Royal Swedish Academy of Music, 2001.

−−−: ‘Musiklivet i Stockholm under Franz Berwalds tid’, in: [pending publication].

Hammar, Bonnie: ‘Oväntat Berwaldfynd − ungdomsopera hittad’, Musikrevy, no. 28 1973.

Hedwall, Lennart: Den svenska symfonin, Stockholm: AWE/Gebers, 1983.

−−−: ‘Franz Berwald (1796−1868)’, liner notes to CD edition, Sterling CDS-1051-2, 2002.

−−−: Oscar Byström. Ett svenskt musikeröde från 1800-talet, Hedemora: Gidlund, 2003.

Hillman, Adolf: Franz Berwald. En biografisk studie. Stockholm: Wahlström & Widstrand, 1920.

Höglund, Jan Lennart: Franz Berwald, tonsättare, ortoped, glasbruksdisponent. Ett liv − en konst. Stockholm: The Royal Swedish Academy of Music, 1996.

Krummacher, Friedhelm: ‘Berwalds Singulière − die singuläre Symphonie’, in: Hans Åstrand (ed.), Berwald-Studien, Stockholm: The Royal Swedish Academy of Music, 2001.

Kube, Michael: ‘Vom Accompagnieren und Accompagniert werden − Berwalds Klaviertrio d-moll aus satstechnischer Perspektive’, in: Hans Åstrand (ed.), Berwald-Studien, Stockholm: The Royal Swedish Academy of Music, 2001.

Lagerbielke, Lina: Svenska tonsättare under nittonde århundradet, Stockholm: Wahlström & Widstrand (distr.), 1908.

Layton, Robert: ‘Det ursprungliga hos Berwald’, Musikrevy, vol. 9, 1954.

−−−: Berwald, Swe. trans. Folke H. Törnblom, Stockholm: Bonnier, 1956. [Eng. trans., Franz Berwald, London: Blond, 1959.]

−−−: Franz Berwald (1796−1868), in: Robert Simpson (ed.): The Symphony, 1966. [Swe. trans. Kajsa Rootzén, Symfoni, Stockholm: PAN/Norstedt, 1975.]

−−−: ‘Berwald: Orchestral Works’, liner notes to CD edition, EMI Classics CDM 5 65073 2, 1977/1994.

Lindgren, Adolf: F. Berwalds ‘Symphonie sérieuse’. Thematisk Analyse, København, n.d.

−−−: ‘Franz Berwald’, Skandinaviske Signaler for Musik, Teater, Literatur og Kunst, vol. 1, 1894.

−−−: ’Franz Berwald’, in: Musikaliska studier, Stockholm 1896.

Lomnäs, Erling: 1796−1996. Franz Berwald 200 år, Stockholm: Svenska rikskonserter, 1996.

−−−: Franz Berwalds Estrella de Soria. Verkhistorik, Källor, Edition av libretto och överblivna nottexter, diss. in musicology, Stockholm University, 2004.

−−−: ‘Weisse Fläche’ im Bilde Franz Berwalds’, in: Hans Åstrand (ed.), Berwald-Studien, Stockholm: The Royal Swedish Academy of Music, 2001.

−−−: ‘Zum Problem der Datierung von Berwald-Manuskripten’, in: Hans Åstrand (ed.), Berwald-Studien, Stockholm: The Royal Swedish Academy of Music, 2001.

Lundberg, Mattias: ‘Några reflektioner över den samtida receptionen av Franz Berwalds musik: Fallet med solokonserterna’, pending publication.

Mankell, Abraham: Musikens historia, vol. 2, Örebro, 1864.

Morales, Olallo: ‘Franz Berwald. Förfäderna. Ur en outgiven Berwaldbiografi’, STM, vol. 3 1921.

−−−: ‘Franz Adolf Berwald’, in: Svenskt biografiskt lexikon, Stockholm: Bonnier, 1924.

−−−: ‘Franz Berwald’, in: Musik, Oslo, 1925.

Nelson, David & Lars Johansson: ‘Franz Berwald (1796−1868)’, liner notes to CD edition with orchestral works, Naxos DDD 8.553051S, 1995.

−−−: ‘Franz Berwald (1796−1868)’, liner notes to CD edition with orchestral works, Naxos DDD 8.553052S, 1995.

Nordberg, Gils Olsson: ‘Kring ett Berwaldmanuskript’, Musikvärlden, vol. 5, 1949.

−−−: ‘Berwald och romantikens konstuppfattning’, Musikrevy, vol. 5, 1950.

−−−: ‘Franz Berwalds resa till Finland och Ryssland 1819’, Musikrevy, vol. 6, 1951.

−−−: (ed.), Franz och Mathilde Berwald. Brev och dagboksblad, Stockholm, 1955.

−−−: ‘Franz Berwald och Börsbalen 1843 vid Carl XIV Johans regeringsjubileum’, Musikrevy, vol. 26, 1971.

−−−: ‘Franz Berwald och musiken vid Karl XIII-stodens avtäckning 5 nov. 1821, ett 150-årsminne’, Personhistorisk tidskrift, vol. 74, 1972.

Norman, Ludvig: ‘Franz Berwalds kammarmusik’, Tidning för theater och musik, vol. 1, 1859.

−−−: Franz Berwald, in Svensk Musiktidning, vol. 2, no. 17, 1881.

Olofsson, Thomas: ‘Franz Berwalds opera Estrella di Soria. Spelversion 1862’, bachelor's thesis, Stockholm University, 1968.

Parrott, Ian: ‘Franz Berwald’, The Musical Times, vol. 95, 1954.

Pergament, Moses: ‘Om Berwalds Estrella di Soria’, Musikvärlden, vol. 4, 1948.

Peterson-Berger, Wilhelm: ‘Ett svenskt tondiktaröde. Franz Berwald’, Musikkultur, vol. 1, 1926, reprinted in: Om musik, Stockholm: Bonniers 1942.

Ringborg, Tobias: ‘Att närma sig Franz Berwalds musik som dirigent och musiker’, pending publication.

Rörby, Margareta: ‘Franz Berwald, Septett i B-dur, stråkkvartett i g-moll’, liner notes to CD edition, Musica Sveciae MSCD 520, 1993.

−−−: ‘Zur Datierung von Berwalds Autograph zum Septett von 1828’, in: Hans Åstrand (ed.), Berwald-Studien, Stockholm: The Royal Swedish Academy of Music, 2001.

−−−: ‘Franz Berwalds samlade verk − utgångspunkter, metodik och resultat’, pending publication.

Schnapp, Friedrich: ‘Franz Berwalds skriftväxling med Franz Liszt’, Ord och Bild, vol. 70, 1961.

Stahmer, Klaus: ‘Ein Beitrag Berwalds zur romantischen Sonatenform. Das Duo für Violoncello und Klavier (1858)’, STM, vol. 59, no. 2, 1977.

Stare, Ivar: Om den musikaliska analysens möjligheter och metod i anslutning till ett studium av Franz Berwalds symfoniska teknik, lic. diss., Stockholm University, 1968.

Sundström, Einar: ‘Till kännedomen om Franz Berwalds operaplaner’, STM, vol. 9, 1927.

−−−: ‘Franz Berwalds operor’, STM, vol. 29, 1947.

Tegen, Martin: ‘Franz Berwalds samlade verk. Några intryck av de hittills utgivna volymerna’, STM, vol. 59, no. 2, 1977.

Törnblom, Folke H.: Symfoniboken, Stockholm: Bonnier, 1948.

−−−: ‘Franz Berwald − Swedish Symphonist’, Musikrevy, vol. 9, 1954.

Waldura, Markus: ‘Der kontrapunktische Stimmtausch in der Instrumentalmusik Franz Berwald’, in: Hans Åstrand (ed.), Berwald-Studien, Stockholm: The Royal Swedish Academy of Music, 2001.

Walin, Stig: ‘Franz Berwalds offentliga konsertverksamhet i Stockholm före utrikesresan 1829’, STM, vol. 28, 1946.

Wallner, Bo: Den svenska stråkkvartetten, vol. 1: Klassicism och romantik. Stockholm: The Royal Swedish Academy of Music, 1979.

Wiberg, Albert: ‘Berwalds musikaliska lånebibliotek’, Vår Sång, vol 11, 1938.

−−−: ‘Franz Berwalds resestipendieansökningar’, STM, vol. 30, 1948.

−−−: ‘Franz Berwald som tidskriftsredaktör’, STM, vol. 36, 1954.

Wibling, Hilding: ‘Ett nyupptäckt porträtt av Franz Berwald’, STM, vol. 11, 1929.

Winterhager, Wolfgang: ‘Die Themenstruktur als Paradigma des Personalstils. Bemerkungen zu den langsamen Sätzen in Franz Berwalds Klaviertrios’, in: Hans Åstrand (ed.), Berwald-Studien, Stockholm: The Royal Swedish Academy of Music, 2001.

Åhlén, Carl-Gunnar: ‘Symfoniker efter sin död − Franz Berwald (1796−1868)’, liner notes to CD edition, Caprice CAP 22032, 1993.

Sources

Göteborgs universitetsbibliotek, Kungliga Biblioteket Stockholm, Musik- och teatermuseet Stockholm, Svenska Akademien, Musik- och teaterbiblioteket, Stiftelsen Musikkulturens främjande Stockholm (Nydahlsamlingen), Stockholms stadsarkiv, Uppsala universitetsbibliotek.

Summary list of works

Operas (Estrella de Soria, Drottningen av Golconda), operettas (Jag går i kloster, Modehandlerskan, Ein ländliches Verlobungsfest in Schweden), orchestral works (4 symphonies, at least 7 tone poems, violin concerto, concerto for two violins and orchestra, piano concerto etc.), chamber music (3 string quartets, 5 piano trios, 2 piano quintets, septet, etc.), songs with piano, choral pieces.

Collected works

This list is a reduced version of the list of works found in Franz Berwald. Die Dokumente seines Lebens, Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1979, pp. 701−717. The works are specified by work title, key signature (where such is mentioned in the original record) and year of composition (alternatively the year the composition was completed).

Stage works

Gustaf Wasa, opera, lost.

Cecilia, opera (?), lost.

Leonida, opera, fragments.

Donna Isabella, opera, fragments.

Der Verräter, opera, fragments.

Estrella di Soria, opera (O. Prechtler), version 1, fragments, 1841.

Jag går i kloster, operetta (F. Berwald).

Modehandlerskan, operetta (F. Berwald et al.), 1843.

En ländliches Verlobungsfest in Schweden, tone painting (O. Prechtler).

Estrella di Soria, opera (O. Prechtler), version 2.

Slottet Lochleven, opera (F. Berwald), fragments.

Drottningen av Golconda, opera (L. Josephson), 1864.

Orchestral works

Symphonies

Symphony in A major, fragments, 1820.

Sinfonie sérieuse in G minor, 1842.

Sinfonie capricieuse in D major, 1842.

Sinfonie singulière in C major, 1845.

Sinfonie (naïve) in E-flat major, 1845.

Concertos and other concert works

Theme and variations for violin and orchestra in B-flat major, 1816.

Concerto for two violins and orchestra in E major, 1817.

Violin concerto in C-sharp minor, 1820.

Concert piece for bassoon and orchestra in F major, 1827.

Piano concerto in D major, fragment.

Piano concerto in D major, 1855.

Tone paintings

Slaget vid Leipzig in D major, 1828.

Humoristisches Capriccio, lost.

Elfenspiel/Älvalek in B minor, 1841.

Ernste und heitere Grillen/Allvarliga och muntra infall in A minor, 1842.

Erinnerung an die norwegische Alpen/Minnen från norska fjällen in F minor, 1842.

Bayadarenfest in A major, 1842.

Wettlauf in C major, 1842.

Other orchestral works

Fri fantasi, lost.

Revûe Marsch for wind orchestra in E-flat major, 1818/1819.

Variationer över Göternas fordomdags drucko ur horn, lost.

Fugue in E-flat major.

Polonaise in D major, before 1843.

Chamber music

String quartets

String quartet in G minor, 1818.

String quartet in B-flat major(?), lost.

String quartet in A minor, 1849.

String quartet in E-flat major, 1849.

Piano quintets

Piano quintet in A major, lost.

Piano quintet in C minor, 1853.

Piano quintet in A major, before 1857.

Piano trios

Piano trio in C major, 1845?.

Piano trio in C major, fragments.

Piano trio in E-flat major, 1849.

Piano trio in E-flat major, fragment, 1849.

Piano trio in F minor, 1851.

Piano trio in D minor, 1851.

Piano trio in C major.

Other chamber music

Quartet for piano, clarinet, bassoon and harp in E-flat major, 1819.

Duo concertant for two violins in A major.

Rondo for two violins in A major.

Sonata for violin and piano, lost.

Duet for two violins, lost.

Septet for clarinet, bassoon, violin, viola, violoncello and double bass in B-flat major, before 1828.

Duo for violoncello or violin and piano in B-flat major, before 1858.

Duo for violin and piano in D major.

Concertino for violin and piano in A minor, fragments.

Works for keyboard instruments

Piano

Andante. Allegro in A major.

Echo in B-flat major.

Polonoise bagatelle in G major.

Thema con variazioni in E-flat major.

Andantino in F major.

Scherzo in E-flat major.

Thema con variazioni in G minor.

Polonoise in E-flat major.

Tempo di Marcia in E-flat major.

Polonoise in A minor.

Polonoise in B-flat major.

Thema con variazioni in E-flat major.

Marche triomphale in A major.

Rondeau bagatelle in B-flat major.

Con spirito in B-flat major.

Poco allegro in D major.

Waltzes, in A-flat major.

Marche triomphale in C major.

Fantasy over two Swedish folk songs in C minor.

Une plaisanterie in E-flat major.

Romance et Scherzo in A-flat major.

Presto féroce in E minor.

Melodicon

Trois fantasies for melodicon, 1. A-flat major, 2. C-sharp minor − E-flat major, 3. A major.

Organ

En lantlig bröllopsfest for organ four hands.

Voice and piano

Three songs, 1817, 1. Glöm ej dessa dagar, 2. Lebt wohl ihr Berger, 3. A vôtre âge.

Romans ('Jag minnes dig').

Romance ('Ma vie est une fleur').

En parcourant les doux climats.

Aftonrodnan (G. Ingelman).

Ute blåser sommarvind (S. Hedborn).

Romance ('Un jeune troubadour').

Mais, ne l’oublions pas.

Romance ('Ah! Jeannot me delaisse').

Le Regard.

Romance ('Ja t’aimerai').

Sång till de närvarande kungliga personerna, 1828.

Des Mädchen Klage (F. v. Schiller).

Traum (L. Uhland), 1833.

Konung Oscar! (G. Ingelman), 1844.

Svensk folksång (H. Sätherberg), 1844.

Der Vogel im Walde, lost.

Vid konung Oscars grav ('Julius'), 1859.

Östersjön (prins Oscar Fredrik), 1859.

Coupletter (Wilhelmina Stålberg), lost.

Blomman, 1860, lost.

Eko från när och fjärran with obligato claritnet (F. Hedberg).

Other vocal works

Kantat i anledning av högtidligheterna den 5 november 1821, cantata for orchestra, mixed choir and solo.

Kantat författad i anledning av HKH Kronprinsessans ankomst i Sverige och höga förmälning, cantata for orchestra and soli, 1823.

Serenade, for tenor, clarinet, horn, viola, violoncello, double bass and piano, fragments.

Flagsang for den norske Dampbaad 'Constitutionen' med variationer, for orchestra, lost.

Der Zug nach Jerusalem, oratorium, incomplete, lost. Completed as Gebet der Pilger am heiligen Grabe, for orchestra and male choir, with Swedish text Bön för orgel och manskör [Prayer for organ and male choir].

Konung Carl XII:s seger vid Narva eller Schwedisches Soldatenlied för flöjt, 2 clarinets, 2 horns and soli (H.W. Bredberg).

Gustaf Adolf den stores seger och död vid Lützen, cantata for military band (cornet, Royal Kent bugle, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, tuba), organ, solo and mixed choir.

Nordiska fantasibilder, cantata for military band (flute, 3 clarinets, cornet, 2 trumpets, trombone) organ, solo and male choir.

Gustaf Wasas färd till Dalarna, tone painting for organ, soli and male choir, (Herman Sätherberg).

Apoteos. Musik till N.N.:s minnesfest över Shakespeare, cantata for orchestra, solo and male choir (L.J. Josephson), 1864.

Musik till industriexpositionens invigningsfest den 15 juni 1866, cantata for military band (piccola flute, 2 flutes, 4 clarinets, 6 cornets, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 tenor trombones, 4 trombones, 2 bass tubas, bombardon, timpani, drums) and male choir.

Avskedssång till idoghetens representanter, cantata for military band (piccola fluta, fluta, 4 clarinets, 4 cornets, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, tenor trombone solo, 3 trombones, bass tuba, bombardon) and male choir.

Serenad för manskör eller manskvartett, 1867.

Hymns and hymn arrangements

Hymn for orchestra and mixed choir.

Hymn for orchestra and mixed choir, 1867.

Hymn arrangement for orchestra and mixed choir, hymn by J Schop.

Hymn arrangement for orchestra and mixed choir, hymn by Michael Praetorius.

54 hymn arrangements for four vocal parts, 1868.