Johan Andreas (Andréas) Hallén, born 22 December 1846 in Gothenburg and died 11 March 1925 in Stockholm, was a composer, conductor, music critic and music teacher. After studies in Germany, he became director of music for the Gothenburg Music Society (1872−78) and then a singing teacher in Berlin (1880−82); he also founded the Stockholm Philharmonic Society and was its conductor from 1885 to 1895. He was second conductor of the Royal Swedish Opera (1892−97), conductor of the Southern Sweden Philharmonic Society in Malmö (1902−07) and a teacher of composition at the Royal Conservatory of Music (1909−19). Hallén was a pioneer of New German music in Sweden and his Harald Viking was the first Swedish Wagnerian opera, although such influences gradually waned as Hallén developed a Nordic idiom. He was elected onto the Royal Swedish Academy of Music in 1884.

Life

Life

The early years in Gothenburg, 1846−66

Johan Andréas Hallén was born on 22 December 1846 in Gothenburg. His father, Mårten Hallén (1811−1888), a farmer’s son from Halland, was a priest, and his mother Hedvig Amalia (1815−1878), daughter of ship-owner Anders Leffler the younger, was a member of Gothenburg society. Hallén demonstrated a precocious talent for music and was given piano lessons at home. At the age of 14 he took it upon himself to play organ in Gothenburg’s poorhouse chapel, and was soon being taught organ technique and harmony by Henric Johan Frithiof Seldener (1829−1880), the city’s cathedral organist from 1854 to 1866. During his studies at Gothenburg upper elementary school Hallén founded a music society, which gave a highly acclaimed concert under his directorship, a triumph that persuaded him to devote his life to music.

Student years in Germany, 1866−71

With the financial support of some rich relatives, Hallén, like so many other Nordic composers before him, travelled to Leipzig in April 1866 to study at the conservatory for, amongst others, Louis Plaidy and Ignaz Moscheles (piano) and Moritz Hauptmann and Carl Reinecke (theory and composition) – the same teachers that Grieg had had a few years previously. After Leipzig, Hallén continued his studies in Munich with a one-year course in composition for Joseph Rheinberger, who also instructed him in the art of conducting.

In the autumn of 1869 Hallén returned to Sweden, where he had his debut as a composer with a performance of his piano trio and the piano quartet op. 3 at a meeting of the Kungliga Musikaliska akademien (the Royal Swedish Academy of Music) on 22 October. A few weeks later, movements from the same works were performed at a public concert in Gothenburg. In 1870, Hallén returned to Germany and Dresden to study composition for composer and conductor Julius Rietz. Given Hallén’s early interest in the New German School, it is remarkable that all his composition teachers belonged to the conservative school that favoured the classical tradition, held Mendelssohn as a model, and ignored or even disdained the music of Franz Liszt and Richard Wagner.

Back in Gothenburg, 1872−78

In 1872 Hallén was appointed conductor of the Göteborgs musikförenings (the Gothenburg Music Society’s) newly formed orchestra, a post he retained until 1878, when the orchestra was dissolved following a fatal cut in their receipts from donors. During that time, Hallén was also the leader of the Harmoniska sällskapet (Harmonic Society), which often sang at the orchestra’s concerts. As music director for the society and in charge of the programmes, Hallén, in defiance of the music critics, made an important contribution to the introduction of Wagner’s music in Gothenburg. After Beethoven, Wagner was the most performed composer at the orchestra’s concerts.

The bulk of their repertoire comprised orchestral and vocal extracts from Tannhäuser and Lohengrin, but Hallén also conducted the preludes to Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg and Tristan and Isolde. The position also gave Hallén plenty of opportunity to perform his own music, and it is during this time that he wrote many of his early orchestral works, such as the symphonic poem Fritjof och Ingeborg, the concert overture I vårbrytningen and the romance for violin and orchestra.

In Berlin and Harald Viking, 1878−83

In the autumn of 1878 Hallén travelled to Berlin, where he met the German writer Hans Herrig (1845−1892). At Hallén’s initiative, Herrig prepared an opera libretto based on Danish author Adam Oehlenschläger’s tragedy Hagbarth og Signe. Back in Gothenburg in 1879, Hallén composed the music, extracts of which were performed at three concerts in the spring of 1880. Following that, Hallén moved to Berlin, where he made a living as a music critic and singing teacher. It was now that Hallén and Herrig discovered that there already was an opera based on the same material, Hagbarth und Signe by the ‘Hungarian Wagnerian’ Ödön Mihalovich (1842−1929) − a composer whose life, works and position in the annals of music resemble in many ways those of Hallén. So the pair changed the protagonists’ names to Harald and Siegrun and the title of the opera to Harald der Wiking.

In the summer of 1880, Hallén toured Germany trying to drum up interest in the new work at different opera houses. In August, he travelled to Weimar with recommendations from the Leipzig opera, where he played Harald der Wiking for a complimentary Franz Liszt. Harald der Wiking received its premiere in Leipzig on 16 October 1881, produced by Angelo Neumann and with a young Arthur Nikisch conducting. The work received an overwhelmingly positive reception from Wagnerian critics, but was slated by the anti-Wagnerian press. Much to Hallén’s disappointment, Harald der Wiking failed to establish him as a composer in Germany and he returned to Gothenburg, where he began to devote his energies to having the opera staged at the Kungliga Operan (the Royal Opera) in Stockholm.

Harald Viking (Leipzig 1881). Scene from Kungl. Operans (the Royal Opera) performance 1912. (Musikverket).

Conductor and composer in Stockholm, 1884−1901

Harald der Wiking was premiered at the Kungliga Operan in February 1884 in Swedish translation (by Adolf Lindgren) under the name Harald Viking. That autumn Hallén moved to Stockholm and formed a choir, the Filharmoniska sällskapet (Philharmonic Society), which he directed from 1885 to 1895. During this time, Hallén performed many contemporary choral works, as well as extracts from Wagner’s Parsifal (1888). He also made pioneering efforts to introduce early music in Stockholm, and in 1890 conducted the first Swedish production of J.S. Bach’s St Matthew passion (albeit reworked and abridged) and the year following Heinrich Schütz’s The Seven Words of Jesus Christ on the Cross.

For the five years between 1892 and 1897, Hallén was second conductor at the Kungliga Operan, where he conducted the Swedish premiere of Wagner’s Die Walküre in 1895. In the 1890s, Hallén also returned to opera, composing Hexfällan (1896) and Waldemarsskatten (1899), the latter of which proving a particular success with a run of 65 performances before vanishing from the repertoire after the 1922/23 season; it remains the fourth most performed Swedish opera at the Kungliga Operan ever. Valborgsmässa (1902), the full-length revision of Hexfällan, was, however, a fiasco that was withdrawn after just two performances.

In Malmö and back in Stockholm, 1902−26

In 1902 Hallén moved to Malmö, where he founded and directed the Sydsvenska filharmoniska sällskapet (Southern Sweden Philharmonic Society) for five years. Together, they gave choral and orchestral concerts not just in Malmö but in many other towns and cities in the south and west of Sweden too, as well as in Copenhagen. It was during his Malmö years that he composed Ett juloratorium (1904), one of his most popular and successful choral works. In 1907, Hallén returned to Stockholm, where he resumed his career as a music critic, this time on Nya Dagligt Allehanda. He was also a teacher of composition at the Musikkonservatoriet (Royal Conservatory of Music) from 1909 to 1919 (becoming professor in 1915). His students included Kurt Atterberg, Oskar Lindberg and Viking Dahl. Hallén, who had been a radical pioneer of new musical trends in Sweden in the 1870s and 80s, now appeared to his students as the face of anachronistic fustiness. And Hallén’s reviews of his students’ works after graduating indicate that he found it hard to accept the new styles that they were introducing. Hallén died at the age of 78 in his Stockholm home on 11 March 1925.

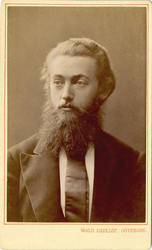

Andreas Hallén 1902. Photo Carl A Olausson. (Musikverket).

Works

From a historical perspective, Hallén’s operas are his most important works, especially Harald Viking, which is the first Swedish opera to be wholly conceived on Wagnerian principles. Other than this, the predominant compositional genres in Hallén’s oeuvre are orchestral and choral works. After his early chamber works he spurned the genre, and, with a couple of exceptions, composed nothing for solo piano either. He did, however, write a large number of songs, primarily for solo voice and piano but also with orchestral accompaniment, as well as two duets.

Operas

Hallén’s Harald Viking (composed 1878−80) is designated an opera rather than a music drama, but its librettist Hans Herrig stressed that he followed Wagner’s ideas on music drama to the letter, and simply used the term opera because it was the shortest and most suitable for the genre (Herrig, who was a personal acquaintance of Wagner’s, was probably aware that he, Wagner, himself rejected the term music drama).

After the 1911 revival, Peterson-Berger claimed in his review of Harald Viking that ‘[i]n all other respects, it is most likely unique in the history of music: I would say that few, if any, are so endowed as to achieve such an uninterrupted and consistent citing of a supremely provocative exemplar.’ Critical hyperbole this might be – and it must be read in light of Hallén’s critique of Peterson-Berger’s Arnljot the previous year − but Wagner’s influences in Harald Viking are extensive and obvious: three acts full of Wagnerian situations and events, alliterative verse, continual dramatic dialogue, leitmotifs and modulating chromatic harmonies. And on top of all this, numerous allusions to specific Wagner works.

In both the reception he received at the time and in later musicology, opinions differ as to whether it was the earlier Wagner (The Flying Dutchman, Tannhäuser and Lohengrin) or the later (The Ring, Tristan and Die Meistersinger) upon which Hallén modelled his Harald Viking. The truth lies somewhere in between. Herrig’s alliterative verse is constructed in the same way as in The Ring and Hallén’s setting of it follows Wagner’s pattern. There are some independent number-like sections (in which Herrig uses end rhymes), such as Gutmund’s ‘Vårsång’ (Act I) and ‘Sång om Valhall’ (Act II). But Gutmund is a singer at the court of Queen Bera and these numbers are songs in the fictional world, echoing Wagner’s Die Meistersinger, for instance, and the singing contest part of its story. Hallén uses some 20 leitmotifs in Harald der Wiking, many more than the six recurring leitmotifs in Lohengrin, yet substantially fewer than those in Wagner’s late works. There is also much less symphonic development of the motifs in Harald Viking then in even the early parts of The Ring.

Despite his reputation as the ‘Swedish Wagner’, Hallén was no uncritical Wagner devotee. His letters to Herrig during the composition of Harald Viking contain several disparaging comments on The Ring and Tristan. In a review from 1890 Hallén warns that the adoption of exactly these late Wagner works for unconditional emulation leads only to mimicry. According to Hallén, a composer’s middle period is often a safer bet for his successors, and that independent imitations of Tannhäuser, Lohengrin and Die Meistersinger could be a way of propelling the art of opera forward to new stage in its evolution. Since Die Meistersinger was composed after Tristan Hallén’s reasoning might seem a little confused, but once the idiosyncrasies of the former are considered, it does make a degree of sense.

While Hallén makes no mention of Harald Viking in this review, the opinions he expresses can be seen as indirect criticism of certain elements of this, his first opera. The style and the Wagnerian references are very different in Hexfällan (1896) and Waldemarsskatten (1899), both of which Hallén designated ‘romantic operas’ (as well as Valborgsmässa, 1902, the revised and extended version of Hexfällan), which underlines the link with Tannhäuser (‘grand romantic opera’) and Lohengrin (‘romantic opera’). The greatest difference between his later operas and Harald Viking is the more central position of the vocal melodies. Hallén held the human voice as the most glorious instrument in existence, so it was natural for him to let his characters vent their emotions themselves, rather than have the orchestra do it for them. Consequently, only a few leitmotifs appear in Hexfällan and Waldemarsskatten and are used not symphonically but only sporadically when warranted by the demands of the plot.

"Waldemarsskatten" premiered 1899 in Stockholm. The cover page is from the printed German version from the same year, with the title "Waldemar".

Orchestral works

Most of Hallén’s 15 or so orchestral works are single-movement, and he avoided traditional genres, such as the symphony. In imitation of Liszt, he composed four symphonic poems, the first ever by a Swedish composer. Hallén opposed detailed and narrative programmes, and, like Schumann, found the programme to Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique disingenuous. With reference to Wagner, Hallén maintained that the programme should only ‘hint at the poetic intentions of the tone poem, not describe them in such elaborate detail as to fetter the imagination of the listener.’ Most of the remainder of Hallén’s orchestral works are also in some sense programmatic, but he did compose two rhapsodies, of which the second − 20 years before Alfvén’s Midsommarvaka − is based on Swedish folk tunes.

Arnold Bäcklin's "Dödens ö" (die Toteninsel) was performed in several different versions. This showing the Basel version from 1880.

Choral works

For much of his musical career, Hallén worked as a choir conductor, so it is not surprising that the 20-plus choral works are the dominant compositional genre in his output. While many of these works are for choir (with or without soloists) and orchestra, there are also pieces for choir and other instrument (such as piano or organ), and some a cappella pieces. In his first choral work, Vom Pagen und der Königstochter for soli, choir and orchestra (premiered in Dresden in 1872) his use of harmony and instrumentation exhibits influences of the New German School, a feature that becomes particularly salient on comparison with Schumann’s setting of the same poem (op. 140, 1852). During his time as director of the Filharmoniska sällskapet in Stockholm (1885−95) Hallén performed choral works from the Renaissance era’s di Lasso and Palestrina to new works by Brahms, Liszt and Verdi. The experience he gleaned from this broad repertoire is also reflected in his own choral works, in which his Wagner influences are blended with other sources of inspiration into a more personal idiom. Another consequence of this is that the choral facture becomes more varied after having been dominated, in the early choral works, by homophonic four-part harmony.

Reception and significance

As a composer, conductor and critic, Hallén was an important trailblazer in Sweden of the New German music being pioneered by Wagner and Liszt. The Swedish premiere of Harald Viking in 1884 established him as a composer in Stockholm, heralding a couple of highly successful decades. After the turn of the century, however, he began to be overshadowed by the upcoming generation of composers, namely Alfvén, Stenhammar and Peterson-Berger − the last of whom, as an influential critic, was one of Hallén’s fiercest detractors. Hallén represented a style that was considered increasingly outmoded, as became even more patent during his final years when modernism began to make headway on the Swedish musical scene.

Joakim Tillman © 2016

trans. Neil Betteridge

Publications by the composer

Musikaliska kåserier (collected reviews, 1894)

Bibliography

Carlsson, Anders: ‘Handel och Bacchus eller Händel och Bach?’: det borgerliga musiklivet och dess orkesterbildningar i köpmannastaden Göteborg under andra hälften av 1800–talet, Gothenburg: Tre böcker, 1996. diss.

Herlitz, Daniel: ‘Ett kaos af skrik och signaler’: något om Wagnerstriden i Stockholm, Andreas Hallén och operan ‘Häxfällan’, C-level thesis in musicology, Stockholm University, 1997.

Hilleström, Gustaf: Andreas Halléns operor: Harald Viking, Hexfällan, Waldemarsskatten, Valborgsmässa, lic.-diss., Uppsala University, 1945.

Josephson, Magnus. ‘Andreas Halléns opera Valdemarsskatten’, in: Ord och Bild, vol. 8, no. 5, 1899, pp. 278–280.

Klinckowström, Axel: Klinckan berättar om böcker och vänner, Stockholm: Bonnier, 1934.

Knust, Martin: ‘“Klappern und wieder klappern! Die Leute glauben nur was gedruckt steht.”: Andréas Hallén’s letters to Hans Herrig: a contribution to the Swedish-German cultural contacts in the late nineteenth century’, in: Svensk tidskrift för musikforskning, vol. 93, 2011, pp. 33–76.

Lindgren, Adolf: ‘Andreas Hallén’, in: Svensk musiktidning, vol. 4, no. 4, 1884, pp. 25–26.

Norlind, Tobias: ‘Andreas Hallén’, in: Ur nutidens musikliv, vol. 3, no. 1, Jan. 1922, pp. 1–7. Includes works list.

Percy, Gösta: Grunddragen av Wagnerrörelsen i Sverige under dess första skede från omkr. 1857–omkr. 1884.

Pergament, Moses: ‘Andreas Hallén, Wagnerianen’, in: Svenska tonsättare, Stockholm, 1943.

Schröderheim, E: Tal vid Andreas Halléns jordfästning, Stockholm, 1925.

Tegen, Martin: ‘Tre svenska vikingaoperor’, in: Svensk tidskrift för musikforskning, vol. 43, 1961, pp. 12–75.

Vretblad, Patrik: Andreas Hallén, Stockholm, 1918.

Åkerhielm, Annie: ‘Vännen Andreas Hallén’, in: Folke H. Törnblom (ed.), Musikmänniskor: personliga minnen av bortgångna svenska tonsättare, Uppsala, 1943, pp. 41–48.

Sources

Bergen off. bibliotek, Göteborgs Universitetsbibliotek, Kungliga Biblioteket Stockholm, Lunds Universitetsbibliotek, Musikmuseet Stockholm, Statens Musik- och teaterbibliotek, Stiftelsen Musikkulturens främjande Stockholm (Nydahlsamlingen), Stockholms stadsarkiv, Uppsala Universitetsbibliotek, Örebro stadsbibliotek.

Porträtt: Kungl. Musikaliska akademien, Nationalmuseum.

Summary list of works

4 operas (Harald der Wiking, Hexfällan, Waldemarsskatten, Valborgsmässa), incidental music for 6 plays, orchestral music (4 symphonic poems, 2 rhapsodies, 4 suites, 2 homage marches, etc.), approx. 12 works for choir and orchestra (most with soli), 6 works for choir and other instruments (piano, organ, etc.), 3 works for a cappella choir, approx. 30 songs with piano (and some duets), approx. 10 songs with orchestra.

Collected works

Operas

Harald der Wiking (H. Herrig), 1878−80. Premiere Leipzig 1881 (Stockholm 1884).

Hexfällan (F. Hedberg), 1894−95. Premiere Stockholm 1896.

Waldemarsskatten (A. von Klinckowström). Premiere Stockholm 1899.

Valborgsmässa (E. von Enzberg), 1899−1900. Premiere Stockholm 1902. Expanded and reworked version of Hexfällan.

Incidental music

Over Evne (B. Björnson), Svenska teatern 1886.

Seklernas nyårsnatt (G. af Geijerstam), Svenska teatern 1889 (composed under the pseudonym John Ander).

Kungens födelsedag, Svenska teatern 1889 (composed under the pseudonym John Ander).

Den vandrande juden (drama in 12 tableaus based on E. Sue’s novel), 1889. [For Svenska teatern, but the play was never produced (Svenska teatern was sold by compulsory auction in February 1890 and was transferred to new ownership).]

Gustaf Vasas saga (D. Fallström), Kungliga Operan 1896.

Sancta Maria (Z. Topelius), Visby 1901.

Det otroligaste (K.-E. Forsslund), Svenska teatern 1901.

Orchestra

Frithiof och Ingeborg, symphonic poem op. 8, 1872.

Huldigungsmarsch op. 10. Premiere Gothenburg 1873.

I vårbrytningen, concert overture op. 14, 1876.

Rhapsodie no. 1 op. 17. Premiere Stockholm 1882.

Rhapsodie no. 2 (Svensk rapsodi) op. 23. Premiere Berlin 1882.

Ein Sommermärchen/En sommarsaga, symphonic poem op. 36, 1889.

I skymningen, tone poem for string orchestra op. 40 no. 2. Premiere Stockholm 1891.

Ur Waldemarsagan, suite for orchestra [no. 1], 1891. 1. I Dagbräckningen, 2. Waldemarsdansen (Bourrée), 3. Ung Hanses Dotter, 4. Svarthäll.

Im Herbst (Om hösten), Zwei lyrische Tonbilder für kleines Orchester op. 38, 1894. 1. Mondeszauber (Elfdans i skymningen), 2. Traumbilder im Dämmerungsschein (Drömbilder i skymningen). Premiere Stockholm 1895.

Gustaf Vasas saga, suite for orchestra [no. 2], 1897. 1. Das Morgenroth der Freiheit (Vorspiel), 2. Die Vision, 3. Aufruf zur Wehr, 4. Der Einzug (Wasamarsch) 5. Per aspera ad astra.

Die Todteninsel, symphonic poem op. 45, 1898.

Svensk hyllningsmarsch, 1904.

Orchestrasvit no. 3, ‘Scénes poetique’, 1902. 1. Im Frühling – Au Printemps – Våren, 2. Waldesidylle – Idylle dans la Forêt – Skogsidyll, 3. Sylphentanz – Danse des Sylphes – Elfdans, 4. Intermezzo – a la Rococo [sic] – Gavott, 5. Volksfest – Divertissement populaire – Folklifsbild. Premiere Malmö 1902.

Sphärenklänge, symphonic poem, 1905.

Svit no. 4. 1. Ballad, 2. Scherzo 3. Idyll, 4. Feststämning. Premiere Stockholm 1915.

Solo instrument and orchestra

Romance for violin and orchestra op. 16, 1875.

Choir and orchestra

Vom Pagen under der Königstochter (E. Geibel), for soli, choir och orchestra op. 6, Premiere Dresden 1872.

Traumkönig und sein Lieb (E. Geibel), för sopransolo, choir och orchestra op. 12. Premiere Göteborg 1876.

Das Schloss im See (Trollslottet), ballad för choir och orchestra op. 32, 1886. Premiere Stockholm 1889.

Styrbjörn starke (H. Tigerschiöld), för solo, men’s choir och orchestra op. 34, 1888.

Botgörerskan (I. Damm), för sopransolo, choir, stråkorchestra och orgel op. 39, 1890.

Julnatten, för sopransolo, choir, stråkorchestra och orgel op. 41. Premiere Stockholm 1895.

Dionysos (F. Åkerblom), kantat för soli, men’s choir och orchestra. Premiere Göteborg 1901.

Ett juloratorium (A. Åkerhielm), för soli, choir och orchestra, 1904.

Festkantat för industriutställningens i Norrköping invigning (G. Malmberg). Premiere Norrköping 1906.

Sverige, festkantat för soli, choir och orchestra op. 50. 1. Urbygden (G. Malmberg), 2. Till fädrens minne (G. Malmberg), 3. Saga i folkviseton (Afzelius och Geijer), 4. Väktarrop (Motett) (Oscar Fredrik [=Oscar II]), 5. Hymn till fosterlandet (G. Malmberg). Premiere Stockholm 1908. [Utökad och omarbetad version av Festkantat för industriutställningens i Norrköping invigning.]

Requiescat (E. Fredin) för solo, choir och orchestra op. 54, 1909

Choir and other instruments

Drei Lieder för damkör och piano op. 24. 1. Die Osterglocken/Påsk-klockorna (A. Böttger), 2. Die Wasserrose/Vattenliljan (E Geibel), 3. Lockung/’Hör du ej’? (J. v. Eichendorff). Pub. 1884.

Das Aehrenfeld (H. von Fallersleben), for women’s choir and piano op. 25, 1880.

Vineta, rhapsodi för mans- och kvinnoröster med ackompanjemang av orgelharmonium och piano op. 26, 1882.

Kyrkokörer. Tre andliga sånger för blandad kör med ackompanjemang av orgel. Pub. 1913.

Requiem for solo soprano, double choir, orchan and celesta or piano, 1917.

Missa solemnis for soli, choir, organ, harp (or piano) and celestas, 1920−21. Premiere Stockholm 1923.

Choir a cappella

Tre körvisor op. 19 for mixed choir a cappella. 1. Söfd af himlen vhilar jorden, 2. Drömmen, 3. Vårsång.

Drei Motette op. 20. 1. Peccavi super numerum, 2. Gloria, 3. Requiem.

Körer a cappella för mansröster op. 30. Pub. 1885.

Svenska folkvisor och dansar op. 37. Premiere Stockholm 1889.

Philharmonie (anon.) for solo and eight part mixed choir a cappella op. 42. Premiere Stockholm 1891.

Chamber music

Piano trio C minor, 1868.

Piano quartet D minor op. 3, 1869−70.

Piano

Ballad, 189.

Songs

Sechs Lieder op. 2, 1870−71. 1. Liebespredigt (F. Rückert), 2. Der Mond am Himmel lacht (unknown), 3. Der Mond ist aufgegangen (H. Heine), 4. Stiller Abschied (F. Dingelstedt), 5. Volkslied (E. v. Geibel), 6. Aus dem ‘Lyrischen Intermezzo’ (H. Heine).

Sånger för baryton op. 11. 1. Die Bergstimme (H. Heine), 2. Vesper (J. v. Eichendorff). [Year of composition unknown, but the opus number suggests that the songs are composed between 1873 and 1875.]

Visor för sopran op. 13. 1. Nattlig Sång/Nachtlied (E. v. Geibel), 2. Majsång/Mailied (J.W. v. Goethe), 3. ‘Får jag dina ögon se’/’Wenn ich in deine Augen seh’ (H. Heine). Pub. 1876.

Drei Lieder för alt eller baryton op. 21. 1. Abseits. Ballade (H. Seidel), 2. ‘Am Wege’ (M. Kalbeck), 3. Herbstabend (M. Kalbeck). Pub. 1883.

Drei Lieder op. 22. 1. Mailied (C. Brentano), 2. ‘Vergiss mein nicht’ (C. Brentano), 3. ‘Es winkt des Königs Töchterlein’. Ballade. Pub. 1883.

Tre duetter för hög sopran och mezzosopran (eller tenor och baryton) op. 27. 1. Zwiegesang, 2. Der Engel, 3. Volkslied. Pub. 1889.

Tre visor af Gellerstedt för sopran op. 29 (A. Gellerstedt). 1. ‘Det fins en gosse och han är min, 2. I skogen, 3. ‘Och många tusen kronor’. Pub. 1885.

Skogsrået, ballad för mezzosopran eller tenorbaryton och orchestra op. 33 (V. Rydberg). Premiere Köpenhamn 1888.

Junker Nils sjunger till lutan för baryton och piano eller orchestra (D. Fallström), 1896. [From the incidental music to the saga of Gustaf Vasa.]

Två dikter av Viktor Rydberg för mezzosopran och baryton. 1. Jungfru Maria i Rosengård, 2. En blomma. Pub. 1899.

En visa till Karin när hon hade dansat (G. Fröding, ur Kung Eriks visor). Pub. 1900.

Tre sånger för mezzosopran eller baryton med liten orchestra. 1. En visa till Karin (G. Fröding, ur Kung Eriks visor), 2. Romans ur ‘Sancta Maria’ (Z. Topelius), 3. Jungfru Maria i Rosengård (Viktor Rydberg). Orchestration and compilation of earlier composed songs. Premiere Stockholm 1901.

Sånger för mezzosopran och baryton med piano eller orchestra, 1903. 1. Bacchanal [Feststämning]/Beim Feste (E. v. Geibel), 2. Serenad/Serenade (E. Lembcke), 3. Höststämning/Herbstgedanken (E. v. Geibel), 4. Julisol (M. Krook). Höststämning och Julisol. Premiere Malmö 1903.

Drömmen (E. Lembcke) for tenor and piano. Pub. 1908.

Stenbocks kurir, ballad för baryton och piano eller orchestra (C. Snoilsky). Pub. 1909.

Tre visor i folkton med piano eller liten orchestra. 1. Jungfrun i det gröna (B. E. Malmström), 2. Hvad björken gömde (E. Fredin), 3. Visa ur ett sagospel af Topelius (Z. Topelius). Pub. 1909.

Norrland, duett för sopran och tenor op. 55 (A. A. Grafström). Pub. 1909.

Legender och visor för mezzosopran eller baryton (O. Levertin). 1. Gudule 2. Monika 3. Visa ‘Öfver granarnas kronor’. Pub. 1910.

En visa om mig och narren Herkules för baryton och piano eller orchestra (G. Fröding), 1913.

I solnedgången (G. Fröding) for solo voice. Premiere 1913.

Till min sångmö (M. Krook) for tenor and piano or orchestra. Pub. 1916.

Svenska fosterländska sånger och visor op. 57. 1. ‘Varer Svenske’ (D. Fallström), 2. Bohuslänssång, 3. Fiskarfolkets sang, 4. ‘Så hafra’. Visa och dans från Blekinge, 5. Orsapolska från Dalarna, 6. Polska från Dalsland, 7. Hönsgummans visa. Lite’ svensk historia, 8. Svensk fosterlandssång (D. Fallström). Pub. 1916.

Skön jungfru sjunger i högan loft (V. Modin) for voice and piano. Pub. 1924.

Other

Den unge Herr Sten Sture: Melodram och Sorgmarsch för orkester op. 35 (H. Tigerschiöld). Premiere Stockholm 1889.